In the rich tapestry of ancient Egyptian mythology, few deities capture the imagination quite like Anubis. Known as the god of embalming and the caretaker of the underworld, Anubis played a pivotal role in the religious beliefs and rituals of ancient Egypt during the First Dynasty and well into the Middle Kingdom.

During the First Dynasty of Ancient Egypt, Anubis held a prominent position as the overseer of the afterlife. He was intimately associated with the practice of mummification, a sacred process of preserving the deceased for their journey to the hereafter. However, as time passed and the Middle Kingdom era emerged, Anubis’s role was somewhat eclipsed by the ascension of Osiris, who assumed the mantle of the ruler of the underworld. Anubis then shifted his focus towards escorting souls to the afterlife and participating in the “Weighing of the Heart” ceremony.

In the ancient Egyptian lexicon, Anubis was known as Anpu or Inpu, signifying “the royal child” and “to decay” respectively. He was also referred to as Imy-ut, loosely translated as the “Guide to the Damned,” and nub-tA-djser, which means the “Lord of the Sacred Land.” These various names allude to his multifaceted role in the Egyptian belief system.

Anubis was initially considered the son of the sun god Ra in the earliest myths, but later, he was reimagined as the offspring of Osiris and Nephthys. Notably, Anubis played a crucial role in the resurrection of Osiris, who was slain by Seth. His involvement included the mummification and revival of Osiris in the realm of the afterlife, where Osiris would become the king of the underworld. This connection solidified Anubis’s status as the patron deity of embalmers and the conductor of funeral rites.

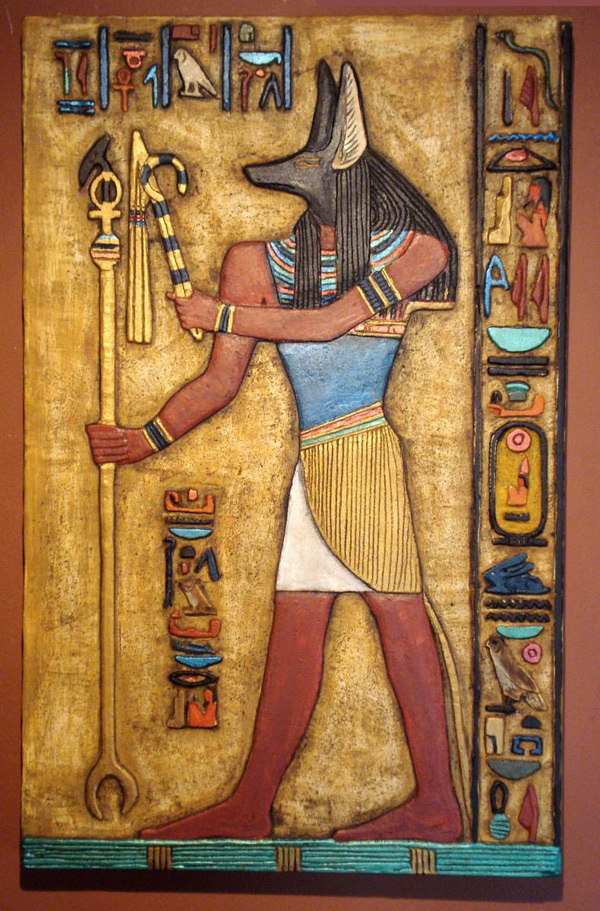

Anubis is often depicted as a man with the head of a black jackal, symbolizing death and decay, which was of great significance in ancient Egyptian culture. However, the color black, associated with Anubis, also signifies rebirth, life, the fertile soil of the Nile River, and the color of corpses after mummification. Consequently, his visual representation frequently incorporates the color black and items related to death, such as bandages used in the mummification process. Anubis’s sacred animal is the golden jackal, also known as the Egyptian wolf.

Anubis played diverse roles in the transition from life to death. He could guide souls to the afterlife, determine their fate, or simply protect their remains. Hence, Anubis earned a reputation as a god of death, the embalmer, and the guide of lost souls.

Anubis played diverse roles in the transition from life to death. He could guide souls to the afterlife, determine their fate, or simply protect their remains. Hence, Anubis earned a reputation as a god of death, the embalmer, and the guide of lost souls.

To this day, archaeological evidence has yet to uncover any grand temples dedicated exclusively to Anubis. Instead, his “temples” were the tombs and necropolises. The primary centers of his worship resided in Asyut (Lycopolis) and Hardai (Cynopolis). His name can be found in the grand mastaba tombs that date back to the First Dynasty, and some temples dedicated to this deity have been discovered.

One notable discovery is the temple and necropolis of Anubeion, located in the eastern part of Saqqara. During the early dynastic periods, Anubis held a more prominent position than Osiris, indicating his continued significance. This changed with the Middle Kingdom, yet Anubis remained one of the most vital deities in the Egyptian pantheon.

Anubis was a god capable of both helping and punishing humanity. He acted independently, sometimes benevolently aiding individuals, while at other times, he would administer retribution.

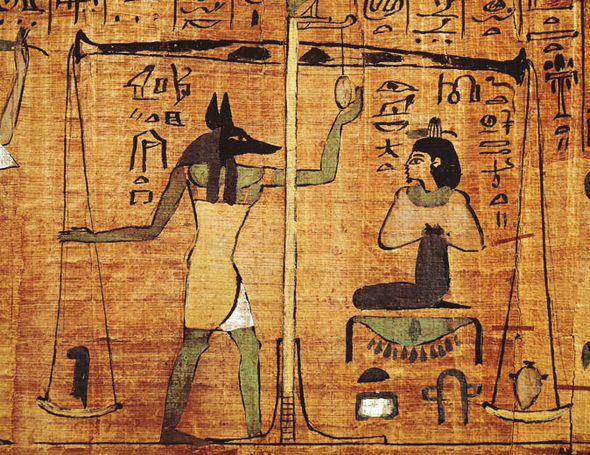

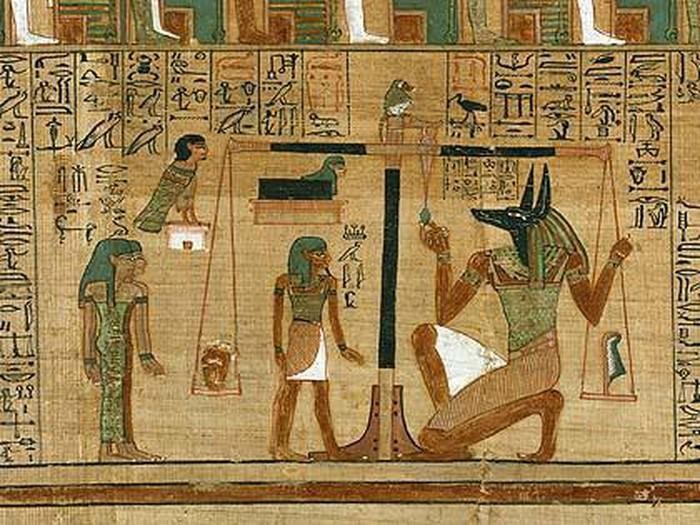

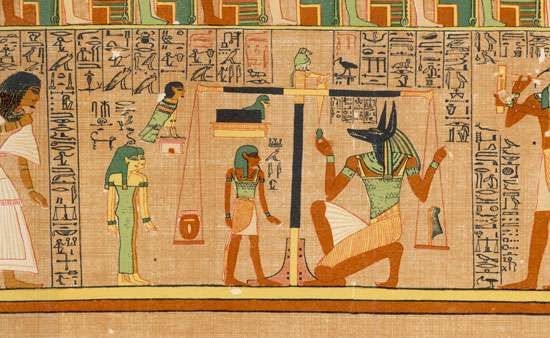

was one of the central aspects of Anubis’s responsibilities. This ceremony occurred after the deceased had been mummified and cleaned, and Anubis was the “Guardian of the Scales.” It was based on the belief that after death, individuals would meet the gods, and their hearts would be weighed against a special feather.

In the Great Hall of Judgment, the soul would declare its innocence by reciting the 42 negative confessions, subsequently purifying itself before the gods: Osiris, Ma’at (the goddess of justice and truth), Thoth (the god of writing and knowledge), the 42 judges, and, of course, Anubis, the god of death.

The ancient Egyptians believed that the heart was the repository of emotions, intelligence, will, and character. A pure heart would enable the soul to enter the afterlife.

Using a set of golden scales, Anubis would weigh an individual’s heart against the feather of Ma’at, the symbol of truth and justice. If the heart weighed less than the feather, the soul was deemed worthy and could proceed to the Fields of Aaru, a place of eternal bliss and serenity. Conversely, if the heart outweighed the feather, indicating a life filled with transgressions, it would be devoured by Ammit, the devourer of the dead, and the individual would face eternal exile and torment.

In this role, Anubis held the power to determine the fate of souls, making him a ruler of the afterlife, second only to Osiris.

Although Osiris took over as the ruler of the Egyptian afterlife, Anubis continued to play a significant role in the world of the deceased. He was seen as the god of embalming, guiding the souls, and safeguarding tombs. According to the legend of Osiris, Anubis helped Isis embalm her deceased husband.

According to this myth, the embalmers working on the mummification process wore jackal-headed masks, a practice that was attributed to Anubis. Additionally, when Osiris was slain by Seth, his organs were sent to Anubis as a gift, sparking the tradition of offering certain body parts of the deceased to the god.

Anubis is typically depicted with a scarf wrapped around his neck, symbolizing protection by the goddesses and representing his protective authority. The ancient Egyptians believed that jackals would protect the buried from scavengers.

Anubis also held the role of the punisher of tomb robbers, a grave offense in ancient Egypt. For those who respected the deceased and lived virtuous lives, Anubis would ensure they found peace and happiness in the afterlife.

Anubis, the jackal-headed deity of ancient Egypt, played a multifac